Hey Governor Shapiro: Recruiting More Doctors Won’t Work

You can’t fix a leaking pipe by forcing more water into it

Late last month, Governor Josh Shapiro of Pennsylvania posted this on Threads:

We’re facing a critical shortage of healthcare professionals — especially in our rural communities.

But we have the power to fix this.

Let’s come together to strengthen our health care workforce pipelines by expanding loan repayment for doctors and nurses who agree to serve our rural communities.

Now, this sounds like a good plan on its surface: a dearth of healthcare professionals, so let’s recruit more healthcare professionals.

Simple, quick, targeted.

Right?

Unfortunately, if the last decade has taught us anything, it’s that Governor Shapiro’s solution isn’t going to work—and it may actually backfire.

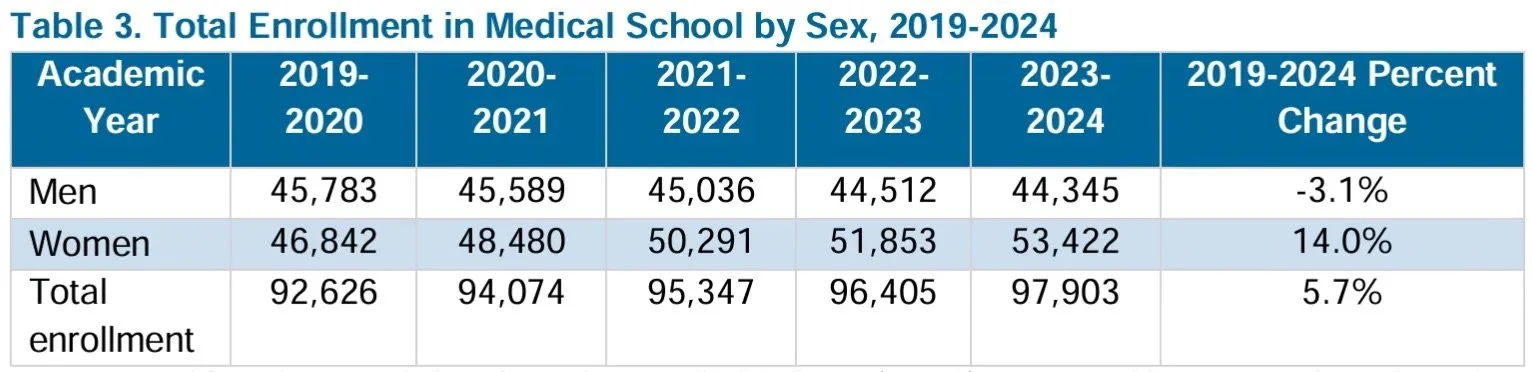

Before I explain why, two important facts. According to the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, we’re recruiting new doctors just fine. The number of medical school entrants has increased nearly 6% since 2019:

By comparison, the US population has grown by only about 1.8% in that time. So, medical school recruitments are outstripping population growth.

And yet.

The US is projected to be short nearly 200,000 healthcare professionals in the next 10 years. That’s despite recruiting tons of new medical students.

What’s happening?

The lead pipe, in the governor’s mansion

Imagine an old pipe. It’s faithfully carried water from a reservoir to your house for decades, making sure your sink works, your shower has enough pressure, your kids have water to drink, and your shower has the pressure it needs.

Over the decades, it’s started to show its wear. As your household’s water needs have gone up, it’s struggled to keep up. Its seams have started to rust and even spring some leaks.

These leaks concern you—from the pipe’s rusted seams shoot jets of water, each under evident pressure.

It’s been going on for a while, this wear on your trusty pipe. But you’ve been oblivious because you could still water your plants, cook for your kids, and take a shower.

Recently, the leak’s gotten bad enough that you can feel it at home. In fact, your shower’s become little more than a dribble, and your kids daily whinge about how long it takes to fill their Stanley cups.

In short, you need more water.

Given the leaks, you’ve got two choices:

Fix or replace the entire pipe

Pump more water into the pipe to overcome the leaks. (In good news, you’ve been friends with Homer, the guy who controls the municipal water supply, since high school. You know what kind of donuts he likes. For a couple dozen of them, he’ll do you a solid.)

And here’s the thing: you could replace the pipe. You know that fixing the leaks is the long-term, sustainable solution. But there are a ton of problems with doing that, not least of which is that it’s insanely costly. So much more costly than a box of donuts!

It’s also a lot more complex. Replacing the pipe—or even just fixing each of the leaks—means hiring an entire crew, probably shutting off your water entirely for a while, to say nothing of sourcing a whole new pipe that meets the dozens of regulations your city’s put in place since the last time the pipe was laid.

So much easier to call Homer.

He opens the spigot to your house. And it works.

Sure, the leaks are bigger, but that’s not your concern. Your shower’s working again—Homer’s pushing enough water through that pipe that it overwhelms the leaks and gets you what you need.

For a bit.

Because the pressure head that Homer needs to generate to overcome the pipe’s leaks also increases pressure at those same leaks. Eventually, those leaks will get worse. And the pipe will lose more water. And Homer will need to generate even more pressure.

Unless the pipe gets fixed, all you and Homer are doing is setting up a death spiral.

The supply and demand of worker retention

My whole life, I’ve worked in passion-forward industries. I’ve been a doctor, a university professor, a global public health professional, and an executive for a health charity (and now, I’m a career coach for people who’ve been burnt by these passion-forward industries and are looking for a way out).

All these industries are plagued by remarkably similar worker retention issues.

For example, big-name universities are notorious for not treating their junior faculty well. This isn’t a new thing. People have been posting about it since Blogger was a thing.

And a quote from the Harvard Crimson suggests that this hasn’t changed:

According to many non-tenure-track faculty, the University invests disproportionately more in the former group while neglecting the latter — denying lecturers and preceptors job security, opportunities for independent research, and a voice in decision-making. This approach, they claim, undermines the quality of Harvard’s teaching as well as the well-being of its teachers.

This approach to hiring isn’t limited to universities, either. It’s the same in every ideologically driven industry I’ve worked in. There’s remarkably little need, for example, for the popular, big-name charities or the global health institutions to focus on retention either. They know that people are banging down their doors to join their ranks, to do the cool work, to travel to the cool places, to live purposeful lives.

And from a simplistic economic standpoint, all of this makes sense. When you can rest on the laurels of a centuries-old academic name or on the coolness of the videos your branding department makes, nothing beats the supply-demand mismatch working in your favor.

When I was junior faculty at Harvard, I felt that mismatch. The institution had little reason to make the long-term, costly investment in me if, the minute I pulled up my stakes and left, a dozen others wanted my post.

The same is true in medicine, in global health, in the charity world, and in many of the values-driven professions. In a way that many industries can’t, these fields can rely on an incessant, eager supply of potential newcomers to shore up any leakage they get from frustrated departures.

There’s no need to fix the pipe if Homer’s got a near-limitless reservoir he can tap into.

Mr. Shapiro, replace the pipe

Let’s get back to Governor Shapiro’s post.

Side note, I’m picking on Shapiro not because I have any beef with him. I don’t even live in Pennsylvania. It’s just that his tweet was the most recent incarnation I’ve seen of the US’s decades-long problematic approach to healthcare, one that’ll eventually collapse on itself.

To give Shapiro his dues: He’s correctly picked up on the fact that there’s a dearth of healthcare professionals in rural areas. And he, equally correctly, wants to address that in his state.

As he should. Access to healthcare, health outcomes, and social determinants of health are significantly worse in rural America than they are in the urban centers—and these disparities are getting worse.

So, Shapiro’s right to want to improve access to rural healthcare.

But look at how he proposes to do it:

Let’s…strengthen our health care workforce pipelines by expanding loan repayment for doctors and nurses who agree to serve our rural communities

Shapiro’s taking the turn-the-spigot-up approach. He’s telling Homer, “Hey, dangle a carrot in front of people to get more of them into rural healthcare.”

He’s taking what my marketing friends call a top-of-the-funnel approach. Get enough people into the pipe, the downstream leaks won’t matter.

If Shapiro can lure enough people into the pipe, there’s no need to figure out—or fix—the reasons people are leaving in the first place.

The problem is, the reservoir isn’t limitless. Between 30 and 40% of physicians plan to decrease their patient contact—or leave altogether—within the next two years. The same is true of nurses. And although that number fluctuates year on year, it hasn’t changed substantively since the end of the pandemic.

The US has about a million doctors. That means between 300,000 and 400,000 doctors plan to decrease patient contact over the next two years. The US graduates just under 30,000 doctors every year.

In my coaching practice, I work with health professionals across the spectrum—from nurses to doctors to vets to dentists to PTs to chiropractors—who are mired in burnout.

Each of their stories is different, each is personal. But not a single one of these folks wants to stay in the pipe. They’re all getting out.

Sure, that’s partly a selection bias (after all, you’re not talking to a burnout coach if you’re not burnt out). But still—I have yet to meet a single health professional who goes through my program and decides, “yep, I’m good where I am. I just need to do more yoga.”

They all change what they want to do—some of them cut back on their patient contact, some move into chaplaincy, some literally become cabinetmakers (I’m not making that up).

And that’s because many of us responded to a top-of-the-funnel call, and then entered a healthcare system literally built on the backs of its providers and patients—a system that wrings every ounce of sweat out of them, all in the service of someone else’s profit. In the spectacular words of Danielle Ofri in the New York Times,

I’ve come to the uncomfortable realization that this ethic that I hold so dear is being cynically manipulated. By now, corporate medicine has milked just about all the “efficiency” it can out of the system….

But one resource that seems endless — and free — is the professional ethic of medical staff members. This ethic holds the entire enterprise together. If doctors and nurses clocked out when their paid hours were finished, the effect on patients would be calamitous. Doctors and nurses know this, which is why they don’t shirk. The system knows it, too, and takes advantage.

It’s time, instead, to fix the pipe. It’ll take a bravery on the part of our elected officials that goes far beyond dangled carrots and loan repayments. It’ll take replacing a system built on our backs with one built for sustainability, for retention, and for patients—not for profit.

And look, it’s not a bad thing to turn up the tap. Loan forgiveness? I’m all for it. Governor Shapiro, please implement that. Open the top of the rural medicine funnel.

And then don’t stop there.

Because, at some point, the reservoir will dry.

→ Doctors, nurses, healthcare folks: Is it time for you to make a change? Are you not sure how? Check out my free webinar on creating your Burnout Escape Plan, one science-backed decision at a time, here.

→ Want more weekly content about making the hard decisions with confidence and clarity? Join my mailing list!

→ Ready to transform this insight into action? Get my free guide, “The Anatomy of a Good Decision,” where I break down the exact framework that helped me navigate my transition out of burnout.