I Never Wanted To Be A Doctor, But I Became One Anyway. It Sucked As Much As You’d Think

What happens when your purpose is conquered by your path?

I was a deeply mediocre grade-school student. Except in penmanship. I almost failed that. Drunk crickets trace neater paths through sand than I do with pen on paper.

Sister Viola P, of the Incarnate Word and Blessed Sacrament—a nun who believed in punishing grade-school evildoers by stuffing their butts in wastebaskets—sent my parents desperate entreaties to fix their son’s handwriting.

Thankfully, cursive skill doesn’t play the role in my life they said it would.

To my parents and their friends, though, my penmanship was proof of one very important thing: their son was destined for medicine.

“No!” I’d respond. “I don’t want to be a doctor. I want to be a rock star!” (Because what little boy doesn’t want to be a rock star?) To be honest, I was never going to be a rock star. The first time my dad heard my high-school band’s demo album, all hope he had for his legacy drained from his face.

“What…was that?” he asked.

Other days, I wanted to be a philosopher. (Because what little boy doesn’t want to be a philosopher?) If I wasn’t going to be a rock star, getting paid just to think — and to tell other people how to think — sounded perfect.

Most often, though, I wanted to be a linguist, because what I really wanted to be was a missionary.

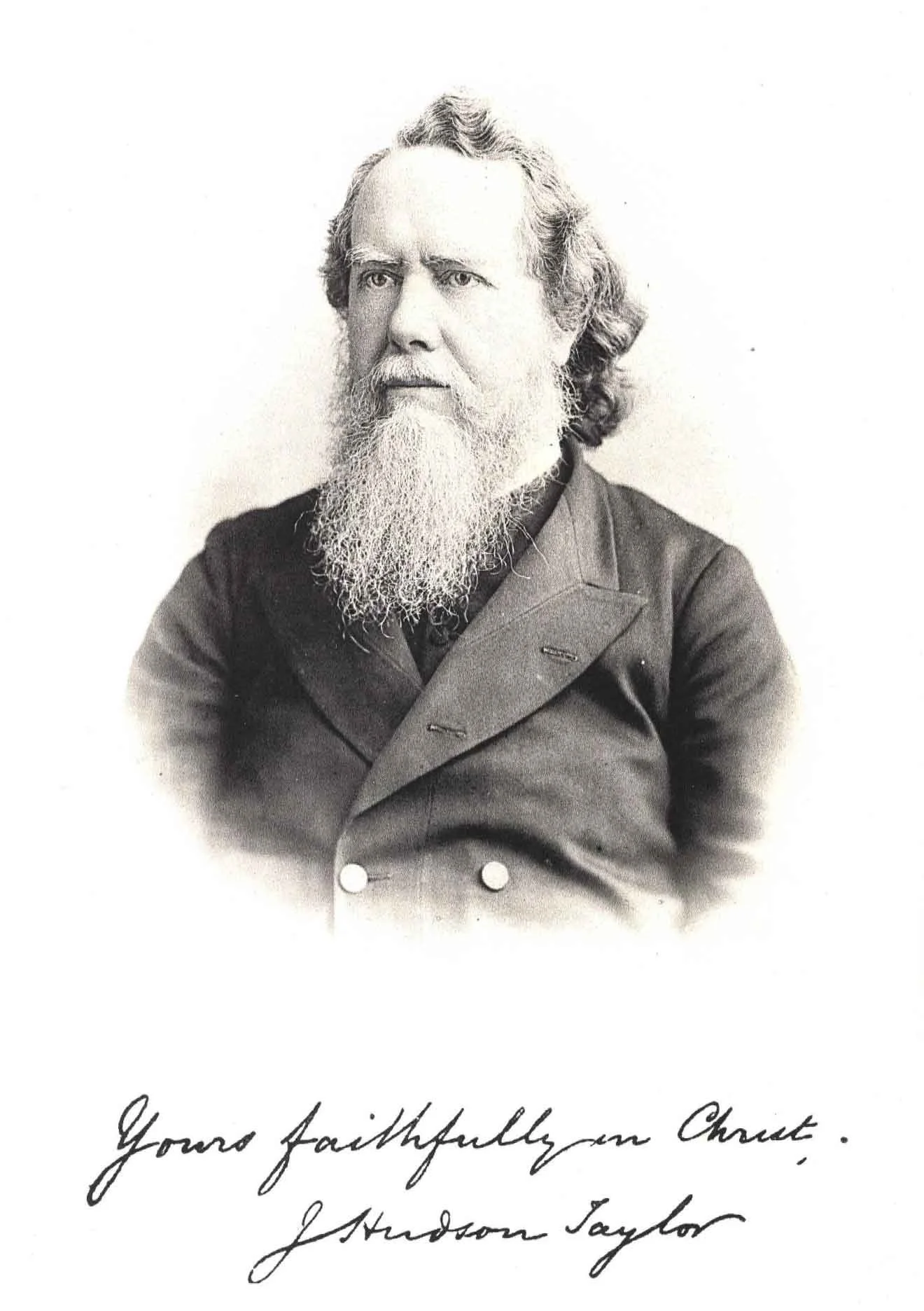

I grew up reading the stories of missionaries: people like Bruce Olson, an American missionary from Minnesota; like Hudson Taylor, a British missionary to China; or like Jim Elliot, the modern-day martyr whose life captivated young Christians in my generation.

Their journeys fit every ethos I grew up under. They were men of faith. They worked hard. They preached to the Other, convincing them to abandon their evil and soul-damning beliefs in favor of absolute truth. They didn’t rust. These men led impressive lives, lives I wanted.

I loved Hudson Taylor the most. I devoured every book I could find on the man. Born in 1832 to a British chemist and a Methodist lay preacher, Taylor spent fifty-one years working as a medical missionary to China. Like Olson, he went all in. On his first posting in coastal China, his dour, black English dress made people call him a “black devil.”

To counter that, he adopted Chinese clothing and the common tonsure-plus-ponytail hairstyle. He also decided that coastal China presented too little of a challenge. He needed to go inland, to spread his message to people he hadn’t yet reached.

Taylor lost his family to China. His daughter, Grace, died of meningitis; his two sons, Samuel and Noel, and his wife, Maria, all succumbed to cholera in the country. He never wavered.

His dedication, his ingenuity—he trained neighborhood cats to be a pest-control army—and his tenacity until his death in 1905 in Changsha all modeled the life I wanted.

He sacrificed his life for his convictions. Nothing could be more noble.

Also, look at that epic beard. (Source)

Crucially, Taylor also never worked in Africa, which was serendipitous, because I never wanted to work on that continent. I’d grown up to view it as Other—as a single, monolithic, dirty place, hot, dry, and infested with bugs.

In other words, I was determined to be a missionary, but on my own terms. During a college mission trip to a Palestinian refugee camp in Jordan, I committed myself to modeling Hudson Taylor’s life specifically. On the flat-topped roof of our homestay, a friend and I leaned over the balustrade, watching the sun set over a dusty city. I told him I wanted to do this for the rest of my life. I was going to be a missionary in Asia.

That night, he and I prayed that God would never send me to Africa. Lol.

Linguistics would be my ticket. It would take me into Asian jungles. I would disappear into Papua New Guinea for decades. I’d create the writing system for a language that had never been written. I would translate the Bible; I’d codify the oral history of a people threatened with extinction; I’d teach them the right way to live; and I’d return only after my work was done. Or I’d die trying. This was my dream.

Linguistics still fascinates me — the sounds we make, how tone confers meaning, why some languages use alphabets and others use syllabaries, how words evolve across time, and why Yoda sounds weird to just about everyone.* I still sometimes read linguistics textbooks before going to bed.

But, I’m the firstborn son of an immigrant family. And first-born sons of immigrant families really only have three options: doctor, lawyer, or failure.

In her controversial book Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, Amy Chua took unapologetic possession of a caricature: Asian parents brooked no foolishness from their children. She defended the demands she and her husband put on their chil- dren, claiming these demands in childhood led to success in adulthood.

East Asian parents don’t have a corner on the tiger mother market. We Lebanese hold our own. Being a rock star, a linguist, a philosopher, or a missionary? Not even worth consideration. My choices were clear: I would carry on my father’s business, or I would go into medicine, the law, or some other respectable entrepreneurial endeavor of my own.

Full stop.

I didn’t want to be a lawyer or a businessman, but I liked science.

So, if it wasn’t going to be linguistics or philosophy or music, then it would have to be science. Still, I didn’t go quietly. On our tour of universities, my dad insisted on visiting every biology lab he could find. With the visceral disinterest of a seventeen-year-old, I stared blankly at the protein gels or the genetically modified fruit fly colonies that were supposed to cure cancer.

I didn’t care.

My poor dad. I forced him to reject so many majors during college, to torpedo so many potential career paths before I finally succumbed. I can’t imagine the conversations he and my mother must have had after every phone call. “I found it, Dad! I’m going to major in music composition! No? How’s psychology, that works, right?”

Each time, he returned to one maxim: no child of his would study a subject whose “only purpose is to perpetuate itself.” His words. Music, philosophy, and linguistics fell under that aegis.

Reluctantly, I capitulated.

Fully 95% of the students graduating from molecular biology where I went to school in the mid-1990s went on to medical training. I may never have wanted to be a doctor, but, every other dream denied, I had no reason not to follow them.

What a strange disrespect for my values that stance is:

Not wanting to be a doctor wasn’t a strong enough reason not to be a doctor.

But, as a college senior, though, I didn’t know better. Doctoring made sense. It was respectable. It satisfied my elders. It had value.

I took the required courses, eked out a passable score on the MCAT, and applied to twenty-five different medical schools.

Of which twenty-three rejected me. They saw what I couldn’t. Despite my superficial assurances that being a doctor would fulfill all my childhood dreams, my heart wasn’t in it, and they sensed it.

They looked behind the tightly crafted personal statements to the ennui that undergirded them. I couldn’t yet articulate that I only applied to medical school because it was acceptable, because it was safe, and because it fit my family’s ethos, but they heard it anyway.

“Success for you,” their rejections said, “can’t be found in our halls. Look elsewhere.”

I didn’t listen.

Let me take a small detour here to talk about success. Success looks different for everyone. True success is individual, and it’s only found at the end of a life lived in service of why.

As a culture, however, we espouse a narrow, monolithic definition of success. According to the story we’re fed, success looks like financial security, a respectable job, and a happy family. It’s such a trenchant story because it simplifies major life decisions. It keeps us from having to solve for why.

And if we don’t have to do the hard work of solving, we’re free to let life happen to us. We can measure success through tan- gible outcomes: promotions, money, children, houses. Because this definition’s simplicity is so alluring, its tendrils insinuate themselves everywhere.

The problem with this monolithic definition lies not in the things it makes us pursue—there’s nothing wrong with money, career success, or a fulfilling family life—but in the fact that, unless these things are actually our why, they end up feeling like a trap.

This kind of success charts a wide, smooth, and well-populated path through the banality of privilege, to a conclu- sion we’re not convinced we actually want. Like lidocaine to our psyches, it numbs us to why.

The wide, smooth, anodyne path is like a moving sidewalk at an airport, as safe as it is boring. It’ll get you to a destination, but once you’re on it it’s almost impossible to get off. And unless that destination is one you actually want, the moving sidewalk does you no good.

On the moving sidewalk, we go to school, sometimes to college, sometimes to graduate school. Then we dive headlong into the churn of a three-decade career. Somewhere in there, we find a spouse to whom we may or may not stay married, have kids to whom we may or may not be devoted, and buy a house whose mortgage we may or may not pay off. And then we exit the churn, bruised, battered, beige, and — sometimes — financially secure. In the words of Dennis Merritt Jones, we “endure until we exit the planet.”

I felt this in medicine.

Doctors trace a prescribed arc from cradle to grave. We kill ourselves to do well in high school so we can win admission to a competitive university, where we kill ourselves to do well (again) so we can apply for medical school. Once we get in, our careers become remarkably pre- fab. Medical school for four years, residency for three to five, maybe a fellowship for another few years, and then practice for thirty. Whether we work for ourselves or join a larger hospi- tal network, we whir through three decades of active clinical life, seeing dozens of patients a day, five days a week. Then we retire with a nice house in a nice retirement community with golf buddies we sometimes like and occasional visits from our grandchildren.

Unless medicine is our why—which, let me be clear, it is for many—we add spice only to the margins. Maybe we do research on the weekends. Maybe we go into administration. Maybe we teach. At the core, however, every doctor’s life looks similar, and for good reason: medicine’s prefab arc leads almost inexorably to financial security, a respectable job, and the banality of privilege.

Medicine has a cotton candy draw, wispy, sweet, ephemeral. To a college senior without a clear sense of his why and without the courage to stand up for where he thought he wanted his life to go, however, it’s ultimately lethal.

Had I been honest with myself, I wouldn’t have applied to medical school. Had I done the work of solving for why, I wouldn’t have started on the moving sidewalk. And had I been honest in my med school applications, I wouldn’t have gotten in anywhere. I wouldn’t have fooled two schools into accepting me.

Instead, I said the things I was supposed to say, wrote the personal statement I was supposed to write, and tried to con- vince the admissions committee that, yes, I really did dream of being a doctor. I made majestic, far-reaching statements about both my potential future and my inner landscape, all with fin- gers crossed — hoping they would reject me so at least I could say I’d tried.

I could articulate none of this in the spring of 1992, as I taped twenty-three medical school rejection letters to the walls of my dorm room. All I knew was that medical school satisfied the obligations of firstborn sons of immigrant families, and, maybe, if I got lucky, I could still play music on the side.

I chose to create a life I never wanted in the first place.

It sucked as bad as it sounds.

Sound familiar?

Does your path no longer fit your purpose? I got out, and I want to help you do the same. Here’s how to work with me:

→ Check out my courses here. They range from 4 weeks to a year, and they take you from “what the heck do I do next” all the way to clarity and a step-by-step plan that honors both your calling and your right to thrive. Click here to apply!

→ Want more weekly content about making hard decisions with confidence and clarity? Join my mailing list!

Footnotes

* Whether it was intentional on George Lucas’s part or not, Yoda’s syntax belongs to a distinctive, and incredibly rare, linguistic typology. Most English sentences adopt a subject-verb-object (or SVO) structure: “I drew a tree,” for example. I is the subject, drew the verb, and tree the object. This is the second-most-common structure globally; 42 percent of the world’s languages have an SVO typology. A bit more common are SOV languages, like Korean or Japanese.

Yoda doesn’t adhere to either of these structures. When he says, “Much to learn, you still have,” he’s using an OSV — object-subject-verb — typology. In the wild, fewer than 1 percent of the world’s languages are OSV, and all come from the Amazon basin.

Interestingly, we English speakers do occasionally use an OSV structure when we want to emphasize certain parts of a sentence. Consider the lyrics to the song “Friendly Persuasion”: “Thee I love, more than the meadows so green and still.” Here, “Thee I love” is OSV, just as Yoda would have wanted it.

** This essay is adapted from Chapter 3 of my book, Solving for Why.