OK, But Maybe You SHOULD Live a Life of Regret

Regret-sensitive decision-making for your big life choices

I sat at the airport café table, my flat white untouched, staring at my phone. I thumbed my passport absent-mindedly. The choices I’d made to get me to JFK that day felt heavy.

Everything in my rational brain told me that nothing about it should feel heavy, but my rational brain had stopped talking to my anxiety somewhere in the TSA precheck line.

“It’s just a flight,” I whispered to myself. “If it doesn’t work out, you can always come back.”

But it wasn’t just a flight. It was the culmination of dozens of decisions — big and small — that took me out of my job, out of the US, chasing a job in a country I’d never lived in like some modern-day Marco Polo. What if I moved and hated it? Worse, what if I didn’t move? What if I stayed put and resented never trying?

What was I supposed to do with all the potential regret?

Could I really YOLO my way through life?

What shall we do about regret?

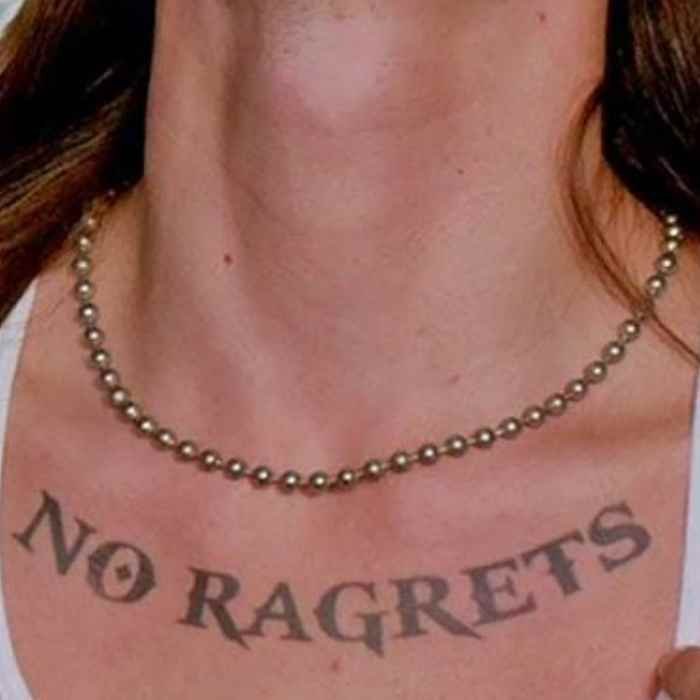

Popular culture harangues us about regret — and specifically how we should always live without it. “Never regret. If it’s good, it’s wonderful. If it’s bad, it’s experience,” as Victoria Holt (apparently) said.

But that’s obviously impossible. It’s a fool’s errand to try to YOLO your way through life.

Last week, I asked my Instagram followers, “What’s your biggest regret?” Since I gave them an anonymous way to answer, they were brutal in their honesty. A small verbatim sampling of their answers:

Getting married when I knew she wasn’t the right person, then staying married too long

Clinging to evangelicalism even when I knew it was harmful because I loved the feeling of belonging

Not pursuing better employment bc of fear of failing

Losing myself in someone else because I was so desperate to be loved

And since living without regret is nigh-on impossible, let’s talk today about how to use one of the most formidable tools in the decision scientist’s arsenal: regret minimization.

It’s me, hi…

Before we can minimize it, we’ve got to define what we mean by “regret.”

In their 2007 paper, A Theory of Regret Regulation 1.0, Marcel Zeelenberg and Rik Pieters argue that regret is a distinct emotional experience — different from sadness or disappointment — because it involves a sense of personal agency. They write:

Regret is the emotion that we experience when realizing or imagining that our current situation would have been better, if only we had decided differently. It is a backward looking emotion signaling an unfavorable evaluation of a decision. It is an unpleasant feeling, coupled with a clear sense of self-blame concerning its causes and strong wishes to undo the current situation

(emphases mine)

In other words, regret comes not only from comparing the outcome of a chosen action to the outcome that would have occurred had a different action been taken. It also comes with a healthy dose of self-blame for having made the “wrong” choice — even if wrong was only in the looking back.

The three types of regret minimization

Alright. Definitions and Taylor Swift out of the way, let’s talk about regret minimization. There are three types.

The first is the fool’s errand we already talked about. Living a life with zero regrets whatsoever. And yeah, there are some crazy people who’ll climb up Yosemite’s Half Dome without a rope just because. But for most of us, our amygdalas don’t allow a full-throated YOLO in the face of life’s big decisions. So, honestly, that’s all the ink I’m going to waste on regret elimination.

The second is best described by the absolutely saccharine 2001 interview Jeff Bezos gave to the Academy of Achievement. In it, Bezos said:

I wanted to project myself forward to age 80 and say, “Okay, now I’m looking back on my life. I want to have minimized the number of regrets I have.” I knew that when I was 80 I was not going to regret having tried this. I was not going to regret trying to participate in this thing called the Internet that I thought was going to be a really big deal. I knew that if I failed I wouldn’t regret that, but I knew the one thing I might regret is not ever having tried.

(emphasis, again, mine)

And look, that’s great. “I did a crazy thing that totally went totally against conventional wisdom and now I’m the second richest person in the world!” is the mating call of phallic-shaped rocket builders. It’s also survivorship bias.

And then there’s the third: find a way to minimize the amount of regret — not the number of regrets — you might face in a big decision. Let’s talk about how to do that.

(Side note: I’m going to give the simplest formulation of regret minimization. With my clients who face big life decisions, I use a much more nimble approach to regret, but the below should at least give you a sense of how to do it. And if you’re interested in diving deeper, grab some time on my calendar here.)

It starts with assigning happiness points to your options.

Imagine, for a second, that you’re a 19th century gentleman of means, tasked with deciding which be-petticoat-ed young lady of similar means should be the unfortunate subject of your charm. (Because this is the 19th century, if you aren’t interested in any be-petticoat-ed young ladies, your only choice is to retire to the countryside with your close friend and the dog that survives you both).

Anyway, Dorothy, Ida, and Harriet top your list.

Harriet plays the piano beautifully, manages a social calendar with surgical precision, and knows exactly how many glasses of sherry each guest has had. She’s not flashy, and you’re ok with that because she’s always five moves ahead. She’s the rare strategist who knows just how the world works. She’ll support your ambitions, remember every important name at the dinner party, and subtly steer conversations in your favor. She’s a true partner.

Or that’s what she’ll have you think — because you’ll never be totally sure who’s running the estate. Harriet may gently poison a rival’s reputation at tea or orchestrate a marriage alliance that serves her interests, and you’ll always wonder if you’re next.

Ida, on the other hand, is sharp-tongued, fiercely intelligent, with a laugh to rival Falstaff. She reads Shelley, rides horses like a man, and can beat most of the household staff at chess. She’s exhilarating. Unlike the simpering daughters of other landowners, she talks politics at dinner and flirts like it’s bloodsport. You imagine candlelit debates, children who quote Rousseau, and a life of passion and adventure.

But also, she will correct you in front of guests. And one day, she might board a steamship to Boston with a suitcase of Elizabeth Cady Stanton pamphlets and zero explanation.

And finally there’s Dorothy. Sweet, sweet Dorothy. She is sugar incarnate. She’s got a voice like gossamer, she embroiders with panache, and her moral compass rivals any temperance pamphlet this side of Manchester. She smells faintly of lavender and piety.

Of course, perfection is dull. Dorothy won’t attend the opera because it’s “worldly,” won’t dance because it’s “immodest,” and won’t ever let you forget that time he took wine with dinner. She’ll never stray, but she’ll never let him forget that he does.

Assuming your primary objective in marriage is to minimize your future regret (because, after all, this is an essay about regret), how do you choose?

Decision theorists have formalized a few ways to choose, methods that minimize the amount of regret you would feel if things go wrong. One of them — the simplest to understand — is the minimax regret principle.

It involves three steps.

First, identify all the outcomes of your options.

Then, score (say, on a scale from 0–10) how much regret you’d feel if that outcome happened.

Then, pick the one with the least regret.

So, for example: Let’s say you’re someone who really values stability, an intellectual equal, and partnership in a relationship—and you’re willing to sacrifice other things for it. Your regret outcomes for the betrothal decision might look something like this:

Harriet:

If the best case happens: Regret = 0. You’ve found a true partner.

If the worst case happens: Regret = 10. That backstabbing would be hard to get over

Ida:

Best case: Regret = 3. That sharp tongue of hers always keeps you guessing

Worst case: Regret = 5. I mean, she left, but what a brilliant reason to!

Dorothy

Best case: Regret = 1. She’s lovely, if maybe a bit too saccharine and pious

Worst case: Regret = 6. Yes, you got stability…and constant judgment

The minimax regret framework would tell you that you should pursue Ida first (maximum regret = 5), Dorothy next (maximum regret = 6), and Harriet last (maximum regret = 10).

That way, you could be certain that you’d look back on your choice and realize that, even if you’re in the Bad Place, and you’re regretting it (and, let’s be honest, she’s also regretting you) — you know that regret is as low as it could have been.

I’ve found regret minimization calculations to be particularly useful when clients have been burned before and, because of that, feel super stuck — how can you make a wise decision when your past wisest decisions led to so much regret? Instead of forcing a toxic positivity on them (“Oh, my dear, but what if you fly?”), this method sets them free from the bondage of past decisions, while still acknowledging their very salient need to not get hurt again.

Regret it till you make it

Decision-making is complex, and there’s a risk to over-minimizing regret. Obsessively avoiding regret can mean missed opportunities, creating even more regret in the long run. This method also doesn’t take into account two important factors: the joy of the best-case scenario, and the probability of either scenario happening. Would your decision change if there were only a 0.005% chance that Harriet back-stabbed?

Decision-making requires balancing courage and caution; it’s not about eliminating regret altogether, but about managing it thoughtfully. After all, all decisions happen under uncertainty, which means that all good decisions involve risk.

Infinitely adaptable, gloriously imperfect

Back at the airport, I boarded the plane. Moved to a new country, in the middle of a pandemic. And, in the end, I did come back. In the end, I did regret the decision to get on that flight. My big decision was one that landed me in regret.

And — hear me out — that’s a very good thing.

I knew when I walked down that jetway that my choice might not lead to happiness. But I also knew the regret of not trying would haunt me more.

This wasn’t just about taking a flight. It was about acknowledging that life always comes with regrets. The key is choosing which regrets you can live with.

Good decision-making is never about perfection. It’s never been and it never will be. It’s never about avoiding regret.

We’re not after perfect decisions. We’re after good ones. We’re after ones that, when we look back on them, remind us that we took risks, and those risks made us who we are.

We are infinitely adaptable, gloriously imperfect creatures.

And that, too — that’s a very good thing.

→ Want more weekly content about making the hard decisions with confidence and clarity? Join my mailing list!

→ Ready to transform this insight into action? Get my free guide, “The Anatomy of a Good Decision,” where I break down the exact framework that helped me navigate my transition out of burnout.

→ And speaking of which: are you a health professional who’s burnt out, but the thought of making a big move feels fraught with potential regret? Check out my free webinar on creating your Burnout Escape Plan, one science-backed decision at a time, here.