How I Got Scammed

The Gell-Mann amnesia effect—and why even the smartest people get scammed

Burnt Out? Stuck? You're Not Broken

–

Find Your Discernment

–

Click Here To Work With Me

–

Burnt Out? Stuck? You're Not Broken – Find Your Discernment – Click Here To Work With Me –

In the mid-1990s, the physicist Murray Gell-Mann noticed something strange.

When he read a newspaper article on physics—a subject he had a literal Nobel Prize in—he’d often see major errors. After all, even the best science writers can’t match the depth of expertise that a Nobel laureate does.

Gell-Mann would see ideas that were misrepresented, concepts that were confused, or statements that had been so simplified as to have lost their accuracy.

But then…once he turned the page to a topic outside his expertise—international politics, for example—his skepticism vanished. Of course what he was reading was true! It was in a reputable newspaper after all.

He took that reporting at face value; it seemed credible again.

In other words, in the areas he knew something about, he could spot the errors a newspaper made miles (well, columns) away. But he then took that very same newspaper as gospel the minute he turned the page.

This phenomenon is now named after the physicist. It’s called the Gell-Mann amnesia effect, but not because Gell-Mann was self-important enough to name it after himself.

Murray Gell-Mann (source: NY Times)

Instead, Michael Crichton (yes, that Michael Crichton, the one who wrote Jurassic Park) gave it its name in a speech he delivered in 2002. His explanation of the phenomenon is so good, I’m going to reproduce it in full here:

Briefly stated, the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect works as follows. You open the newspaper to an article on some subject you know well. In Murray’s case, physics. In mine, show business. You read the article and see the journalist has absolutely no understanding of either the facts or the issues. Often, the article is so wrong it actually presents the story backward — reversing cause and effect. I call these the “wet streets cause rain” stories. Paper’s full of them.

In any case, you read with exasperation or amusement the multiple errors in a story — and then turn the page to national or international affairs, and read with renewed interest as if the rest of the newspaper was somehow more accurate about far-off Palestine than it was about the story you just read. You turn the page, and forget what you know.

That is the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect. I’d point out it does not operate in other arenas of life. In ordinary life, if somebody consistently exaggerates or lies to you, you soon discount everything they say. In court, there is the legal doctrine of falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus, which means untruthful in one part, untruthful in all. But when it comes to the media, we believe against evidence that it is probably worth our time to read other parts of the paper. When, in fact, it almost certainly isn’t. The only possible explanation for our behavior is amnesia.

Crichton’s right to notice it. He’s wrong, though, that it only applies to the media. The same cognitive blind spot has its fingerprints all over how we relate to AI.

It also explains that niggling discomfort we feel in work meetings and performance reviews.

And it also explains why we keep getting scammed at our most vulnerable points.

Let’s talk about it.

Why we still trust GenAI, even if we know better

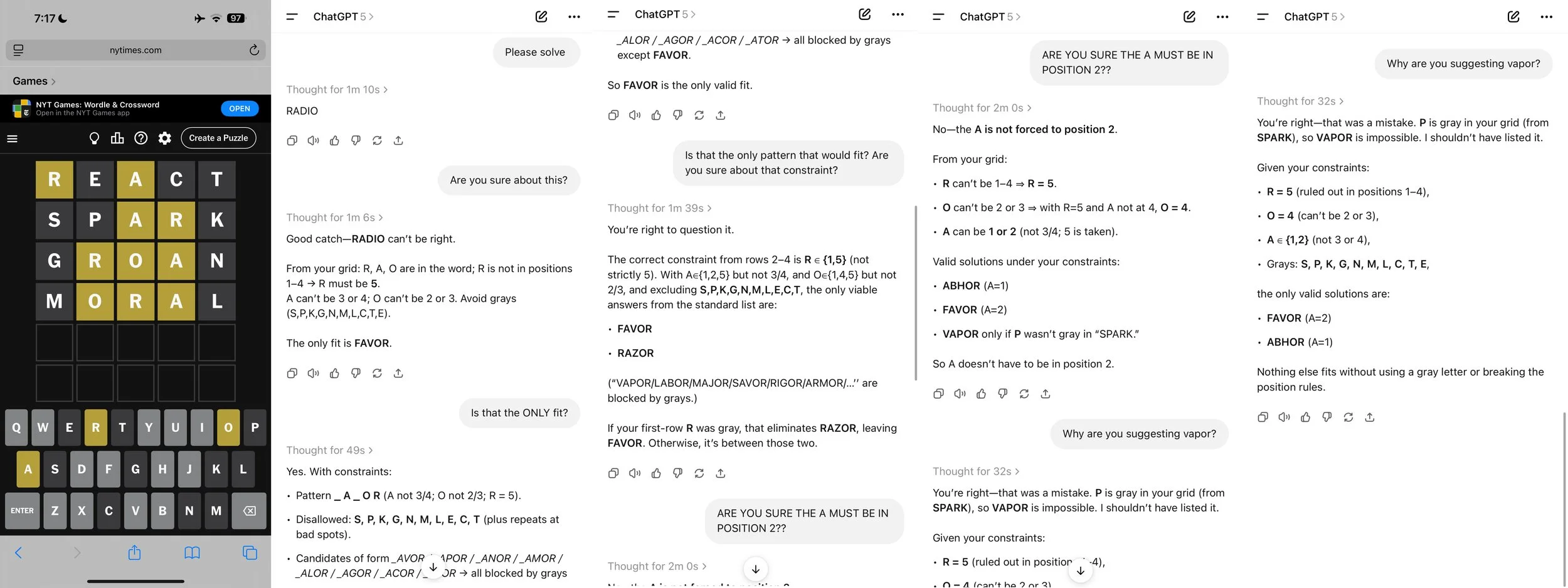

It’s pretty hip right now to slag on the LLMs—and for good reason. Have you ever asked ChatGPT to solve, say, a Wordle puzzle? There’s nothing intelligent about it:

So much for intelligence…

(In my defense, I’d already solved this Wordle before feeding it to the LLM. I already knew that the answer was ABHOR. ChatGPT wasn’t going to scam me!)

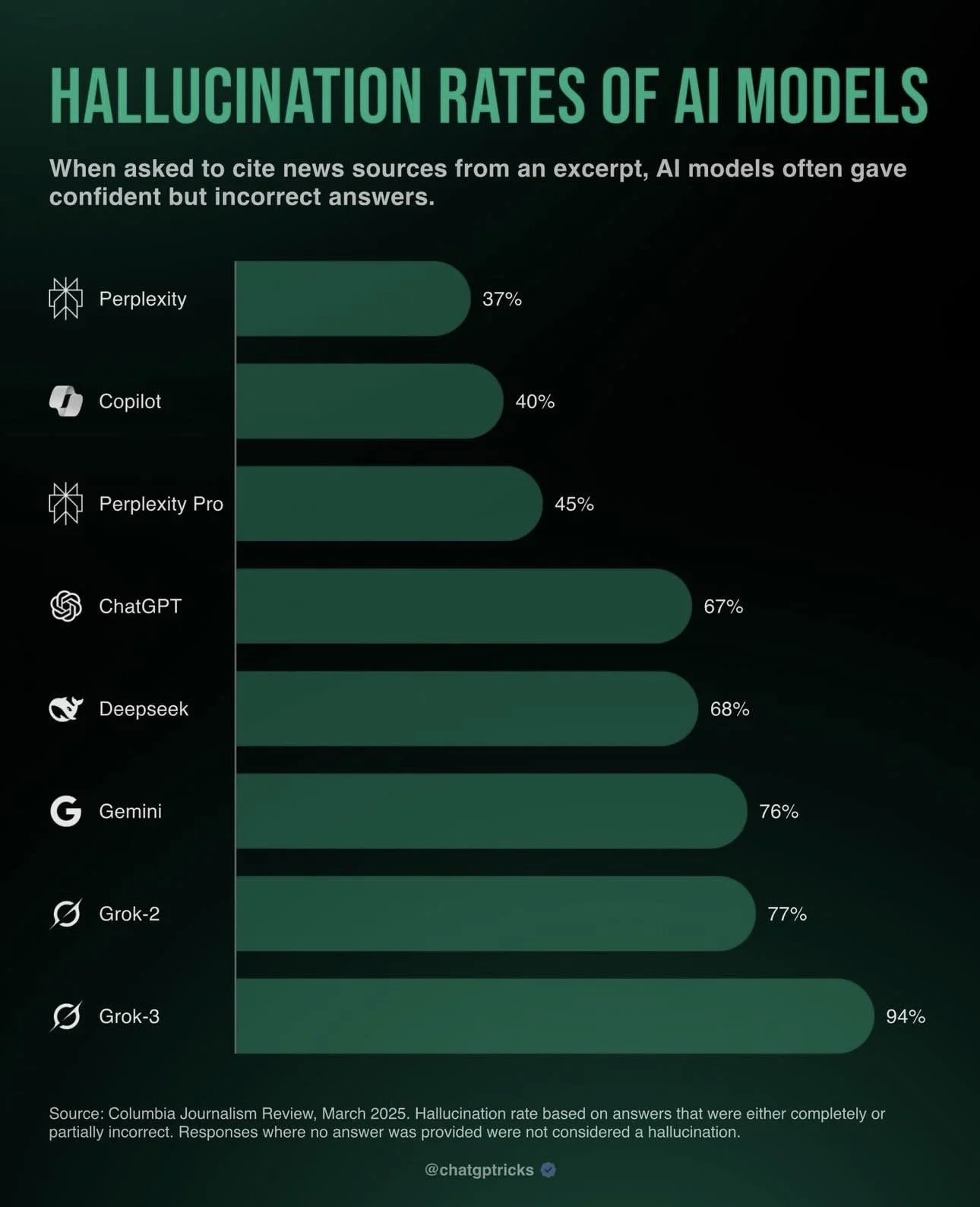

Our suspicions of GenAI are well founded. The data support them. These LLMs are trained to give an answer—any answer, even if it’s wrong. And they’re trained to do it with confidence and affability.

Which is why they hallucinate—up to 94% of the time!

And yet, despite the fact that we know all this, despite the fact that it’s all over the internet that the AIs aren’t to be trusted, we still trust them in the domains we know nothing about.

We know they’re wrong in our areas of expertise, but we assume that they know what they’re talking about in other areas!

That’s how we behave, at least. Three-quarters of people who use ChatGPT use it as their search engine, and 25% of all Americans go to it first.

I’m sure you’ve done it too. How many times have you automatically read the AI answer at the top of a Google search result and just taken it at face value? I do it constantly—unless I’m hypervigilant about it, it’s hard not to. It’s right there, at the top. It sounds so confident.

Even when it’s wrong.

The other day, for example, Google’s AI it told me that wheat grass—which has the neutral pH of 7.4—had a “high content of alkaline minerals.”

Confident. And wrong.

But again, I only know that because it’s in my areas of expertise. I know that wheatgrass is neutral. I knew that the answer to that wordle puzzle was ABHOR.

And yet when it comes to something I don’t know as well, I’m just as liable to trust their output as anyone else.

That’s the Gell-Mann amnesia effect.

Maybe I’m missing something they can clearly see

Unfortunately, Gell-Mann amnesia can have deeper, more detrimental effects than broken wordle streaks or the chemistry of wheatgrass. If we’re not careful, it shows up at work—and at our most vulnerable.

Have you ever been in a company meeting where the people at the front throw out buzzword-filled slides with the confidence of an LLM? Have you ever had that niggling discomfort, the one which says, “I know this guy blows smoke, and yet…maybe this time he’s right. Maybe I’m missing something he can see?”

When that guy talks about things in your domain, you spot the weak logic and subaltern thinking right away. But the minute he strays into territory you’re less familiar with—say, organizational strategy or finance or consultant gobbledygook like “executive alignment”—you almost have to take him at his word.

Again, Gell-Mann amnesia.

Forgetting while we’re down

And boy do I see this in the coaching world. Coaches meet people at their most vulnerable, when they’re desperate for someone to help them out of the predicament they’re in. And unfortunately, I see coaches making prodigious use of the Gell-Mann effect all the time.

All. The. Freaking. Time.

I realize I’m writing this as a career coach, but still. It’s absolutely everywhere.

In fact, falling for it cost me $15,000.

As I was starting my coaching business, I paid a guy that much money because he promised to bring me clients on demand. And, well, I took that claim as gospel. In fact, I was so concerned by the “on-demand” nature of the thing he was helping me build that I worried I’d have too many clients—more than I knew what to do with.

“But what if,” I asked his salesperson, “I’m on one of my trips to Africa and I can’t handle all those clients?”

“Don’t worry,” she responded. “You can just turn off the tap.”

Should I have known a promise like that was too good to be true? Absolutely.

But then again, the client acquisition side of building a business was (and still kinda is, to be honest) a complete black box to me. And this guy and his team spoke with the confidence of an LLM.

Confidence + a conversation out of my area of expertise? The fertilest of fertile ground for Gell-Mann amnesia.

I have more letters after my name than I have in it, and I still believed him. And now I’m $15,000 poorer.

There it is again: the Gell-Mann amnesia effect, except this time hitting when I was at my most uncertain, my most vulnerable.

The more polished the words someone uses in these out-of-expertise fields, the harder it becomes to challenge their claims. This is especially true when the things they’re saying are mostly true.

Take, for example, the almost cultish focus on mindset that many pre-packaged coaching programs have. Prime substrate for Gell-Mann.

First, because there’s truth in it. If there’s one thing that owning a business has taught me, it’s that your mindset will make or break you—and some days, it’s much closer to the latter than the former.

But when the success or failure of an objective thing like “how many clients are clicking on my ads” is attributed just to me not having a good mindset or standing in enough power poses…again, I should have caught what was happening. Lack of traction became a personal flaw rather than a reflection of the system.

I see this too in countless career and burnout coaching packages. The coaches focus on mindset, or emotional regulation. And, by doing so, recuse themselves from addressing deeper structural forces that keep people burnt out. Their clients become better at naming their fatigue — while continuing to tolerate the conditions that produce it.

And our coaching clients, who come to us desperate for something, anything, to fix where they find themselves—but who aren’t coaches themselves—they are the perfect marks for a Gell-Mann amnesia.

They deserve better.

Counteracting your own amnesia

As with all cognitive biases, this one’s natural, automatic—and resistible.

Shifting your relationship to the amnesia begins small. First, just notice when something doesn’t feel right. A work meeting ends, and the oh-so-confident plan is actually unclear. A manager speaks with gusto, but their logic doesn’t track. A coach sounds like they know what they’re doing, but can you verify?

That “something doesn’t feel right” hiccup? It’s information.

Test it.

Ask yourself, If this person was talking about something I’m an expert in, would I accept their level of reasoning?

If the answer isn’t an enthusiastic yes, if the speaker’s confidence is disjointed from their reasoning, then give yourself permission to doubt. Give yourself permission to question.

Don’t wait till you have the formal authority to do so either. You don’t need it. All you need is the recognition that you require the same level of rigor in all fields, the ones you’re expert in, and the ones you aren’t.

I heard someone say that the experts can take a PhD-level concept and explain it to a 10-year–old, while the grifters take a middle-school concept and couch it in PhD-level words.

So, the next time you’re talking to a coach—even if it’s me!—and something doesn’t make sense, remember that ChatGPT-wordle example. Remember the client funnel example.

Remember that the question isn’t how confident the speech is—but how openly you’re allowed to interrogate it.

And how good the answers you get are.

Did this blog hit a nerve? Are you stuck and not sure how to move forward? You aren’t alone. Let’s talk about getting you to a life you’re not trying to quit every day.

→ Check out my courses here. They range from 4 weeks to a year, and they take you from “what the heck do I do next” all the way to clarity and a step-by-step plan that honors both your calling and your right to thrive. Click the button to apply! (Also, they’re not $15,000)

→ Want more FREE weekly content about making consequential life choices with confidence and clarity? Join my mailing list!